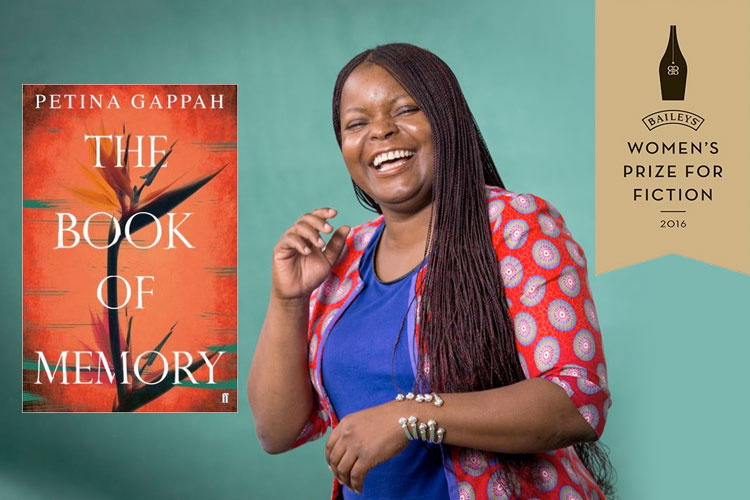

From the Women’s Prize Archives.

Ahead of tonight’s shortlist announcement, we caught up with Petina Gappah, one of this year’s Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction longlisted authors. Read on to find out why Petina decided to base her nominated novel The Book of Memory around a woman on death row in Zimbabwe, her experience of translating Orwell into a native African language for the first time and Petina’s love of Zadie Smith and Jhumpa Lahiri.

While writing The Book of Memory, you moved from Geneva back to your home country of Zimbabwe – why was it important for you to do this?

I went back to Zim for a three-year period between 2011 and 2013 mainly because, at that time, I found it a struggle to be a full time lawyer while travelling to promote An Elegy for Easterly, my first book and also, at the same time, writing my second book all while raising my son Kush. So I went back primarily to rebalance my life and spend more time with my son and family. I had always planned to take a mid-career break at some point, so that period seemed like the perfect moment to do it. The move was really helpful to the novel, there is a lot more ‘Zimness’ in The Book of Memory than in my previous book.

Memory is a finely wrought and incredibly life-like character, where did you get your initial inspiration for her?

Thank you for that compliment. A number of things that I read, remembered and experienced came together to inspire the novel. First was a news story that I read about eight years ago that there was only one woman on Death Row in Zimbabwe. I thought how incredibly lonely and terrifying that must be, to be the only woman in the whole country on Death Row. I wondered what might have brought that woman to that place.

The second thing was a jumbled collection of my own memories of township life in the 1980s, particularly being uprooted from that life and being transplanted in the suburbs where I became one of the first group of black kids to integrate a formerly all-white school in the social transition from Rhodesia to Zimbabwe. I wanted to explore in fiction the experience of that dislocation. So I created a character who had, as part of her childhood, gone though some of the experiences that I had had as a child in addition to an experience that I hope never to have, namely, facing the death penalty.

You’re currently translating George Orwell’s Animal Farm into Shona (the first time Orwell will be translated into an indigenous Zimbabwean language) – why is this an important project for you? Do you have plans to translate any other works?

Animal Farm is one of the best loved novels in Zimbabwe, a whole generation of Zimbabweans studied it in school. When the rights became available a few years ago (Zimbabwe has the standard Berne copyright term of life of author plus 50 years, and not 75 as is the case in the UK) a local newspaper serialised it to the great delight of readers. It is a story that is universal in its depiction of a revolution that eventually soured, a story all too familiar to Zimbabweans.

A group of friends and I thought it would be fun to bring the novel to new readers in all the languages spoken in Zimbabwe. This is important to us because Zimbabwe has been isolated so much in recent years, and translation is one way to bring other cultures and peoples closer to your own.

We have finished the Shona and Tonga translations, which will be published this year. We hope to complete the translation into all the local languages in the coming years. My next project will a Shona version of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. I am also contemplating the daunting task of translating Jane Austen’s Emma, which really should be available in Shona, the characters are so Zimbabwean!

The book is full of fascinating insights into the Zimbabwean prison system; did you do any particular research to enable you to write so convincingly about it?

I relied heavily on anecdotes from people who had been in prison. A few of my friends were in opposition politics and were, at one point or another, arrested on spurious charges under the Mugabe regime. Particularly helpful to me was my friend Tendai Biti, who had been one of my tutors when I was in law school. He gave me a lot of really great details about life in prison, as did other friends, a few of whom would prefer to remain anonymous!

I also read A Tragedy of Lives, a book of short memoir pieces by women who had been in prison in Zimbabwe, edited by Irene Staunton, who runs Weaver Press, the publishing company that distributes my books in Zimbabwe. I was also deeply moved by a series of interviews in the Daily News newspaper by Thelma Chikwanha, a journalist who profiled women who were still in prison. This is really all the research I did.

I did have the opportunity to actually visit Chikurubi Maximum Security Prison but I declined it. It would have required me to sign the Official Secrets Act, which would have meant I could not write about what I saw!

Which writers do you find particularly inspiring?

There are many writers I love but the living writers who inspire me in the sense that I hold them up as models for my own writing because of their work ethic, consistency and commitment to the quality of their work have to be Toni Morrison, JM Coetzee, Kazuo Ishiguro, Zadie Smith, Jumpha Lahiri and Marilynne Robinson. These writers hardly ever seem to have a bad day at the office, and when they do, it is better than the good days at the office for a lot of us!

I also love the Zimbabwean novelist, poet and playwright Charles Mungoshi and the songwriter Oliver Mtukudzi for their commitment to the Shona language and to social justice. If everything goes as I would want it to, I want to be the Oliver Mtukudzi of Zimbabwean writing – I want to tell stores about my country that are global and universal and that spring from the soil of Zimbabwe.