Our fantastic celebrity reviewers champion their favourites from this year’s Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction shortlist. Read on to find out what they made of the six shortlisted books…

Stephen Mangan

The Dark Circle by Linda Grant

Its’s the end of the 1940s and Britain is slowly recovering from the pummelling it received during the Second World War. Attlee’s government is rolling out its socialist agenda, including the creation of the NHS, creating a social mobility never seen before or since. For some, though, the battle is just beginning.

With the arrival of streptomycin and other antibiotics, the corner was turned. The Dark Circle captures the period leading up to this redemption, from drab austerity to an atmosphere of exhaustion, tension and energy.

Twins Lenny and Miriam, Jewish East Enders, are beacons of tenacity and verve among the grey, class-bound inmates of the sanatorium. Then the brashness and pizzazz of the New World erupts in the shape of another life force: rebel American Arthur Persky. The inmates’ multiple narratives are skilfully woven in a beautiful book about a dark world full of irrepressible light. Linda Grant writes with empathy and compassion not just of these battles with a deadly disease but with the battles we all face: the battle to become ourselves, to learn to love, to live with our weaknesses and our battle with our own mortality.

Her book explores society’s ongoing battle with itself to hang on to the opportunities for greater good that the shock of war opened up. Here we are in 2017 and the reemergence of tuberculosis feels like a rebuke.

Danny Wallace

The Power by Naomi Alderman

I’m a sucker for speculative fiction. I love books that ask “What if…?” And there’s something vaguely dystopian in the air these days that tells me the world might be a very different place if the balance of power were tilted in favour of women.

The Power appeals to me on all these levels and more. Having been a teenage boy, I am more than acutely aware of a teenage girl’s power to wound. But in her high-concept social exploration Naomi Alderman throws us into a brave new world in which teenage girls discover the power to inflict agony and death with a flick of their fingers. That power becomes many things: a weapon, a solution, a terror, a relief.

This is an ambitious novel, the kind that will find itself on reading lists in schools and colleges, and you can feel the thrill of the author as she draws from a deep well of inspiration to feed her big idea. It’s a thrill she passes straight to the reader. This is also a book that will have you asking your own questions about the state of the world, the way forward, the true nature of power and the true nature of – well – nature.

Cleverly structured, brilliantly imagined and skilfully written The Power is a compelling and relevant work. Electrifying.

Anthony Horowitz

The Sport of Kings by C. E. Morgan

Having no interest in horses or horse racing I found The Sport Of Kings to be an unappealing prospect. Many consider it to be a great American novel but even that description is off-putting.

I’ve never made it to the end of Moby-Dick. But I needn’t have worried. This is a monumental piece of work and as a writer I found myself breathless in admiration at the scope, the language and the ambition of a book that is, yes, a dynastic saga set in the American south, centring on a horse by the name of Hellsmouth but which actually goes much, much further, tackling black history in the US in a way that is challenging, shocking and urgent.

A sequence in which two slaves escape into Ohio would alone be worth the cover price. An account of the central character, the mixed-race Allmon Shaughnessy, helplessly descending into poverty and crime, is utterly convincing. But almost every sentence sings out. Horses whicker, crickets thrum and summer comes “like an Egyptian plague”.

Morgan’s gaze is universal, almost god-like. The novel is set between the 1950s and the 1980s but reaches back to the Pleistocene age. Her eye sweeps across all America but then settles on the single chromosome of a thoroughbred.

Just occasionally the novel is overwritten. I could have done with fewer tense changes, lists and author interventions. The book is at its best when its brilliantly drawn characters and narrative drive, whether a race riot or a horse race, and sweep you off your feet.

Anita Rani

First Love by Gwendoline Riley

As soon as I finished reading First Love, I wanted to start it all over again. Neve is a smart but needy 30-something writer married to an older man, Edwyn. All of Neve’s relationships are difficult. Her self-absorbed mother leaves her abusive, bullying father then her father dies by eating himself to death.

There are funny moments in the interaction between Neve and her mother but Neve is a product of her dysfunctional upbringing and there is a constant dull ache from the emotional baggage she carries.

Neve reveals her feelings for her American lover in an email and his reply is awkward and painful. Yet she still allows herself to want him.

Most disturbing of all is the cruel, unflinching dialogue between Neve and Edwyn, a misogynist, a master manipulator and a horrible bully. Theirs is a toxic marriage and although Neve is smart enough to see it for what it is, she seems trapped with her husband. And yet by the end of the book, Riley succeeds brilliantly in making the reader sympathise with Edwyn.

Gwendoline Riley is a master wordsmith with a gift for evoking raw emotion from few words. Her short, sharp, succinct sentences skewer the awkwardness and hopelessness of her relationships. Her comedy is dark and her darkness is bleak but if you want a smart and refreshingly honest look at love, relationships and how our past never leaves us this is a very satisfying read.

Bettany Hughes

Stay With Me by Ayobami Adebayo

The joy of the best books is that they cosy up the epic with the mundane. Great writing allows our minds to do what neuroscientists tell us they are physiologically set up to do: to travel across time and space and to imagine ourselves in the hands and hearts of others. Stay With Me does this to the power of X.

In this captivating debut novel we recognise people who fret over the stomach-churning, quotidian tragedies of life while grand tragedies play out around them.

Yejide is desperate to have children. She must also struggle to preserve her marriage against the lure of polygamy and to save her babies, born with sickle-cell anaemia.

This domestic drama plays out against the backdrop of high-octane geo-politics and the stomach-tightening challenges of 1980s Nigeria.

But this sprightly narrative is far from bleak. As well as moments of brilliantly observed comedy (such as breastfeeding a goat to try to coax a womb into fertility), twists and turns in the plot keep the suspense high. The rumbling threat of civil strife and corruption also forces you to care deeply for the characters and, crucially, to respect the age-old power of mother love. With lively dialogue and super-sharp observation Stay With Me is filled with the scent and sounds of jangling Yoruba communities and the back streets of Nigeria as well as with the acrid spoil of stubborn, blind male pride.

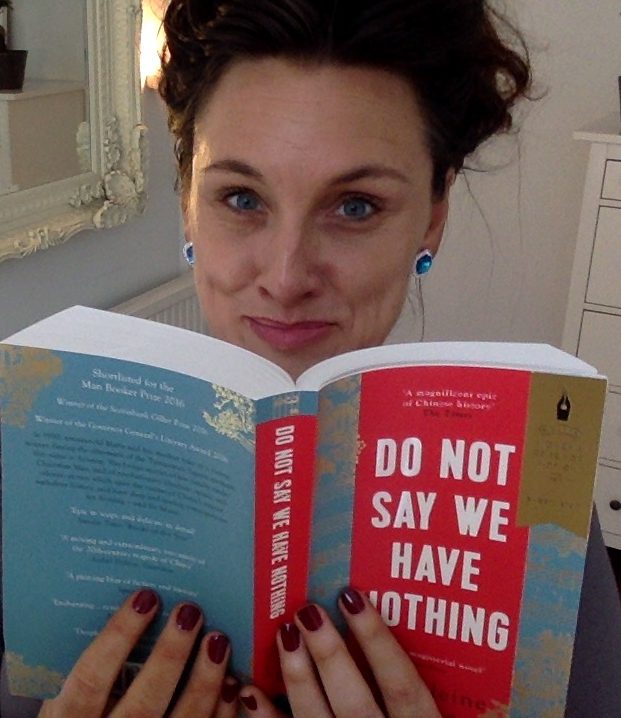

Grace Dent

Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien

In this novel about China’s global diaspora Thien depicts 1960s China in the days before Mao Zedong, moves on to communist one-party rule and the “Great Leap Forward” and then to the distressing scenes of Tiananmen Square in 1989.

Li Ling is a female Chinese-Canadian mathematician living in Canada who sets about making sense of China’s past through folklore, handed-down notebooks and determined questioning. The ancestors whom Li Ling researches are talented musicians, composers, singers and storytellers but they are all living through a political era when their talent was deemed subversive.

Thien’s book asks whether you too would have died for your compulsion to be creative. Or would you have been swept away by Zedong’s vision of a braver, fairer world? Thien writes beautifully and precisely about family ties, mothers and daughters, secrets, shame and duty, its characters faltering between their noble aims and harsh reality as we witness a country consumed by cruelty.

This is not an easy read but the very best literature leaves you viewing the world slightly differently and Do Not Say We Have Nothing echoes and bubbles in the mind long after you have finished it.

Find out more about this year’s shortlist here. And don’t forget to tell us your favourites on Twitter @Womensprize.