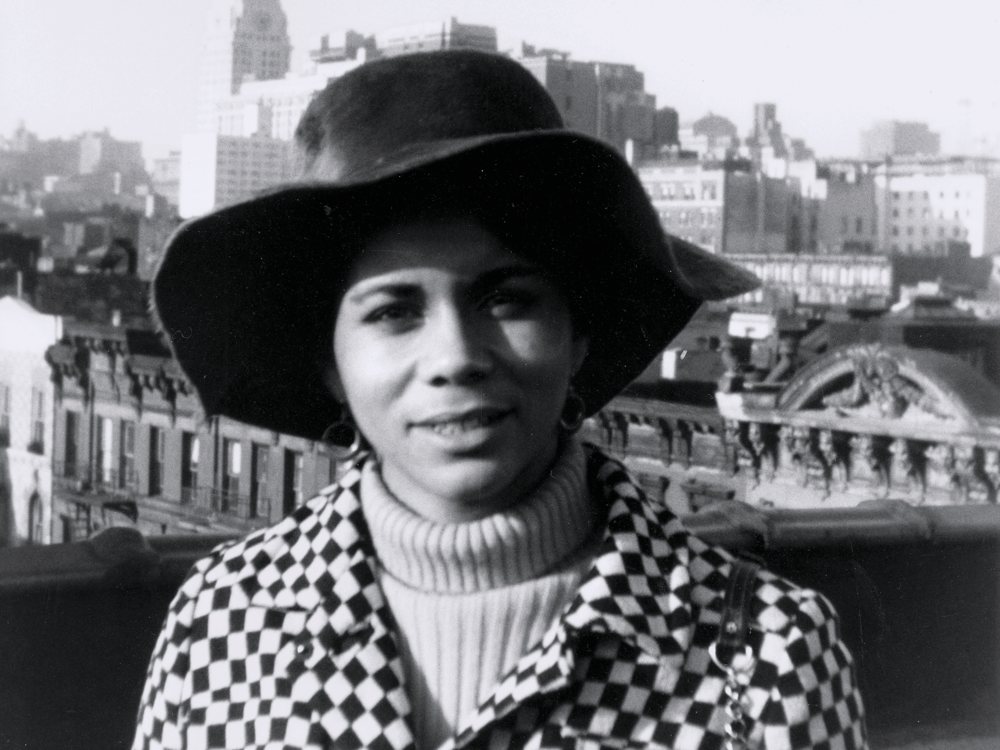

The phenomenal 2019 Women’s Prize for Fiction judge, Arifa Akbar joins us for this edition of Women Writers Revisited to take us into the life of the African-American poet, filmmaker, playwright, writer and civil rights activist, Kathleen Collins (1942-1988) known for her groundbreaking film Losing Ground.

Kathleen Collins was an African American civil rights activist, film-maker, short-story writer, playwright and screenwriter from New Jersey whose abundant talent was unquestionable. And yet, after her untimely death at the age of 46, in 1988, she seemed all but forgotten until her daughter, Nina Lorenz Collins, in 2006, went through her mother’s unpublished works and found stories to publish, and films to restore. It gave Collins a second, posthumous wind which Zadie Smith sums up bittersweetly: “To be this good and yet to be ignored is shameful, but her recovery is a great piece of luck, for us.”

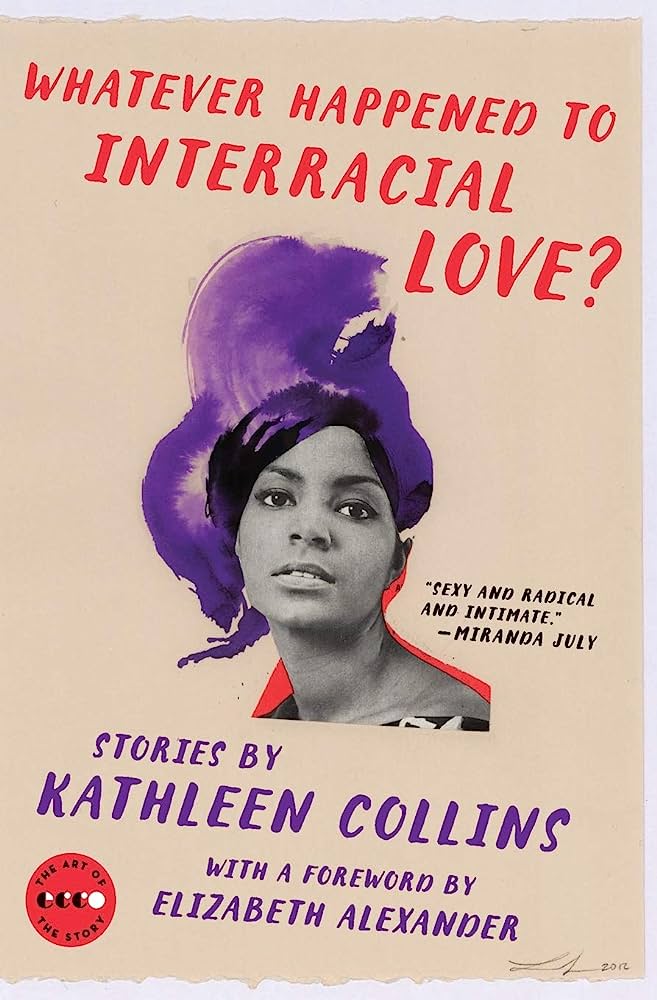

I discovered her writing in 2016 when a collection of her short stories was published under the title Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? There were written in the 1970s and as well as showing the reader so vividly what it meant to live as a black woman – and man – in that time, they struck me as the most subtle, satirical and fluidly-written stories I had read in a long time. Whether they whimsically describe a love affair between a college student and her French professor (“How Does One Say”) or the break-up of a marriage from inside and out (“Interiors” and “Exteriors”) they feel direct, emotionally astute and utterly contemporary. She has both lightness of touch and tender depth, and she creates character and story in a matter of a few pages. In her love stories, and the tales of loss, we find the politics of race and legacy of oppression, but it is captured so masterfully that she barely needs to name it.

The eponymous story, “Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?” has the strongest strain of satire. It draws back to a wide-eyed moment in American history – the year of 1963 – when it seemed suddenly de rigueur – to have “mixed race” relationships. The civil rights movement had kicked in and for it was “the year of race-creed-colour blindness.” Each character introduced in the story comes colour-coded in parenthesis as either (white) or (negro). The characters seek to rise above the nation’s past but we are reminded in these parentheses that it’s not as easy as that.

Still, the story ploughs on, capturing the idealism of the time, when a white boyfriend tells his girl that “I want to be a Negro for you” and when “integration is a pulsating new beat.”

Collins’ satire is delicious even as this high season for integration wanes and dies (“What of all those interracial couples peppering the Lower East Side in the summer of ’63 and the summer of ’64, only to go into furtive decline in the summer of ’65…”).

But it was not for these stories she was known in her lifetime. Her film, Losing Ground, was screened in 1982 and while it was not widely distributed, it was still well received and became a landmark for black women filmmakers in America. Restored and reissued decades later, it was described by The New Yorker as “the great rediscovery of 2015.”

There appears to be a treasure-trove of Collins’ work that the world has yet to encounter. Earlier this year, her letters, diary entries, scripts, and chapters of an unfinished novel, were published in America under the title, Notes From A Black Woman’s Diary.

I look forward to reading more of her words, and her work, but for now, Smith’s words hold true: it is a shameful that Collins was ignored, overlooked, forgotten. And a joy that she is being rediscovery today.

We hope you enjoyed Arifa Akbar on Kathleen Collins. You can read more of our Women Writers Revisited series here.